"Working with artists like Bebe Bérard, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, Vertès, Van Dongen; and with photographers like Hoeningen-Huene, Horst, Cecil Beaton, and Man Ray gave one a sense of exhilaration."

S chiaparelli is the name of an Italian serenade, but it also evokes twelve notes of music that had the fashion world dancing for twenty years. During that time, Elsa Schiaparelli flooded Paris and the world with fascinating collections, each more flamboyant than the last, whose mysterious names continue to resonate today: “Païenne”, “Astrologique”, or “Musique”. Who wouldn’t aspire to be part of such a legacy?

As a child, Schiaparelli grew up against the sprawling background of St Peter’s Square, inspired by the shimmering robes of Vatican princes and the classical antiquity and Renaissance architecture of the Palazzo Corsini in Rome. After coming to Paris, she stated that, for her, designing clothing was not just a profession, but an art form.

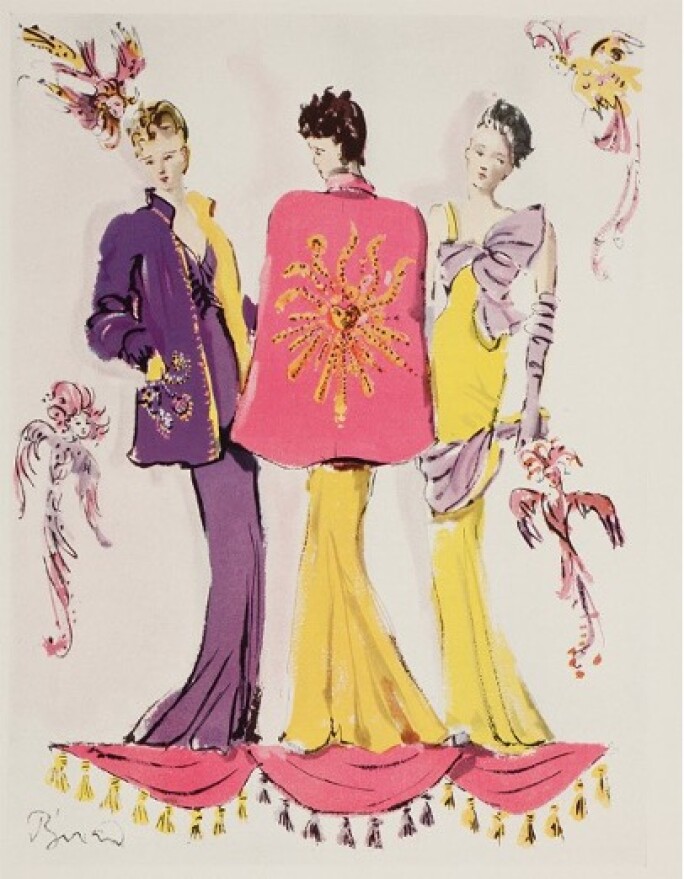

She dominated the fashion world of the Interwar period, collaborating with the most sought-after artists and especially those associated with the Surrealist movement, such as Bérard, Vertès, Drian and Hill, who provided drawings that illustrated her fashion. Man Ray, George Hoyningen-Huene, Horst P. Horst and Cecil Beaton showcased Schiaparelli’s fantastic visions, which were published in the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

Cocteau also worked with the Maison: his line drawings were transposed into cascades of golden embroidery for the autumn 1937 collection. Van Dongen and Dufy transformed Schiaparelli’s daydreams into fashion illustrations, while Vertès and Peynet projected them into captivating advertisements for her perfumes.

In 1939, Elsa Schiaparelli launched her only men’s fragrance, Snuff. It was a daring reference to smoking, a key element of manhood of the time. Following a signature surrealist theme, the bottle was inspired by famous René Magritte paintings and comes in the shape of a pipe while the packaging is in the style of a cigar box.

This circle of artists shared friendship, social relations, and a common desire to break with conventions and push the limits of what is considered beautiful. Schiaparelli managed to orchestrate that balance through her creative process, integrating themes inspired by contemporary events, classical and avant-garde artwork, and aspects of her own psyche. Rather than painting, her means of expression was to be found in plush, lustrous satin, bold prints, and fanciful, outlandish embroideries, not to mention extravagant accessories.

"Here new morphological phenomena occurred; here the essence of things was to become; transubstantiated; here the tongues of fire of the Holy Ghost of Dalí were going to descend."

Her friendship with Dalí was legendary. They worked on several projects together, including the famous shoe hat and the skeleton dress. They intended on sending shockwaves through the public by asserting repulsive images as forms of beauty and redemption, creating a new language through their works. Notably, they featured insects and crustaceans as part of this approach.

The lobster, which Dalí had been exploring through his work since 1934, took on the emblematic form of the lobster telephone in 1936. Schiaparelli’s collection for the summer of 1937 also featured a gigantic crustacean designed by Dalí which was printed along the side and back of a white organza skirt.

According to Schiaparelli, the painter was disappointed that she refused to add what he considered to be the ultimate Surrealist touch: mayonnaise. To Dalí, the lobster was associated with castration, and one might wonder whether Wallis Simpson – who purchased the dress for her trousseau – was aware of its symbolism...